Cutting Electronic Waste out of the Counterfeit Supply Chain

According to the EPA, although electronic waste (or sometimes known as “e-waste”) is less than 10% of the current solid waste stream, it is growing 2-3 times faster than any other waste stream. In 2005 an estimated 26-37 million computers became obsolete and the Consumer Electronics Association reported that roughly 304 million electronics—were removed from US households.

E-waste impacts the international community in many ways. New innovations in industrial and commercial technology have forced obsolescence in equipment like computers, mobile phones and televisions, and refrigerators. As consumers keep up with changing trends, the United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP) estimates that 20-50 million metric tons of e-waste are generated each year and much of this electronic waste gets shipped overseas to developing areas in Asia, Africa, and South America.

The areas impacted by ongoing e-waste dumping often have a high poverty level and don’t have the capacity to manage the e-waste safely. Toxins and substances in electronic waste may include polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), arsenic, and lead.

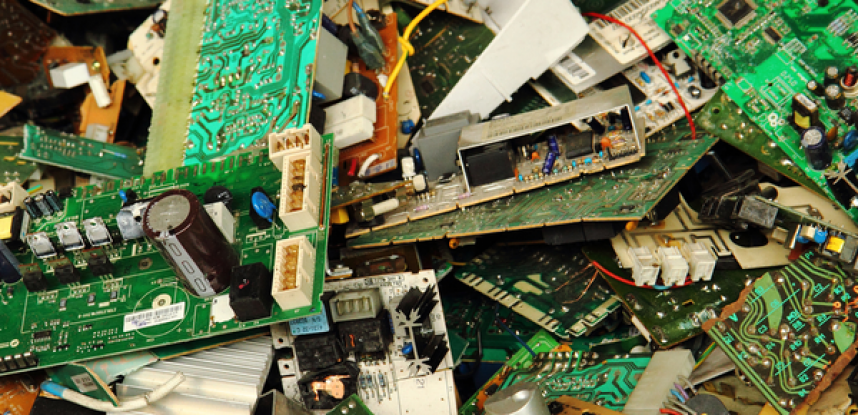

Along with the health and environmental impacts of electronic waste, it is highly reported that electronic waste poses additional threats. Electronic waste is one of the easiest ways for counterfeit and non-conforming parts to enter the embedded supply chain. In fact, the part doesn’t even have to be counterfeit – it could be an original part that had been pulled off an embedded board and sold as new, or an identical part that has resold with a different rating (military vs. industrial).

While most of the latest press on counterfeits has been from the defense industry, preventing counterfeits is important to everyone across the board — from consumer cellphones, to medical equipment, to long-lasting military test systems. According to a recent report from IHS, “on average, more than 1.4 million purchased parts have been involved in suspect counterfeit and high-risk transactions during each year for the past decade.”

In a highly competitive industrial community, obsolescence is a fact of life. But when we look at what it means to have a successful collaborative healthy supply chain, we also need to address what happens to the technology once it is done.

The GDCA Team